In 1986, VAD was crowned Dutch club champion. That same year, an international match was held between a team of ten players from the KNDB and ten from the USSR. There's no need to mention the score by which the Soviets comfortably dispatched the Dutch team — but the players from Amsterdam also got their shot. It was hard to imagine a more honorable gift!

The result was a narrow defeat: VAD vs. USSR, 9–11.

After the match, our guests assured us that VAD had better players than anything the KNDB could have put together… Of course, that was quite an exaggeration — and readers can judge for themselves by checking the data on Toernooibase.

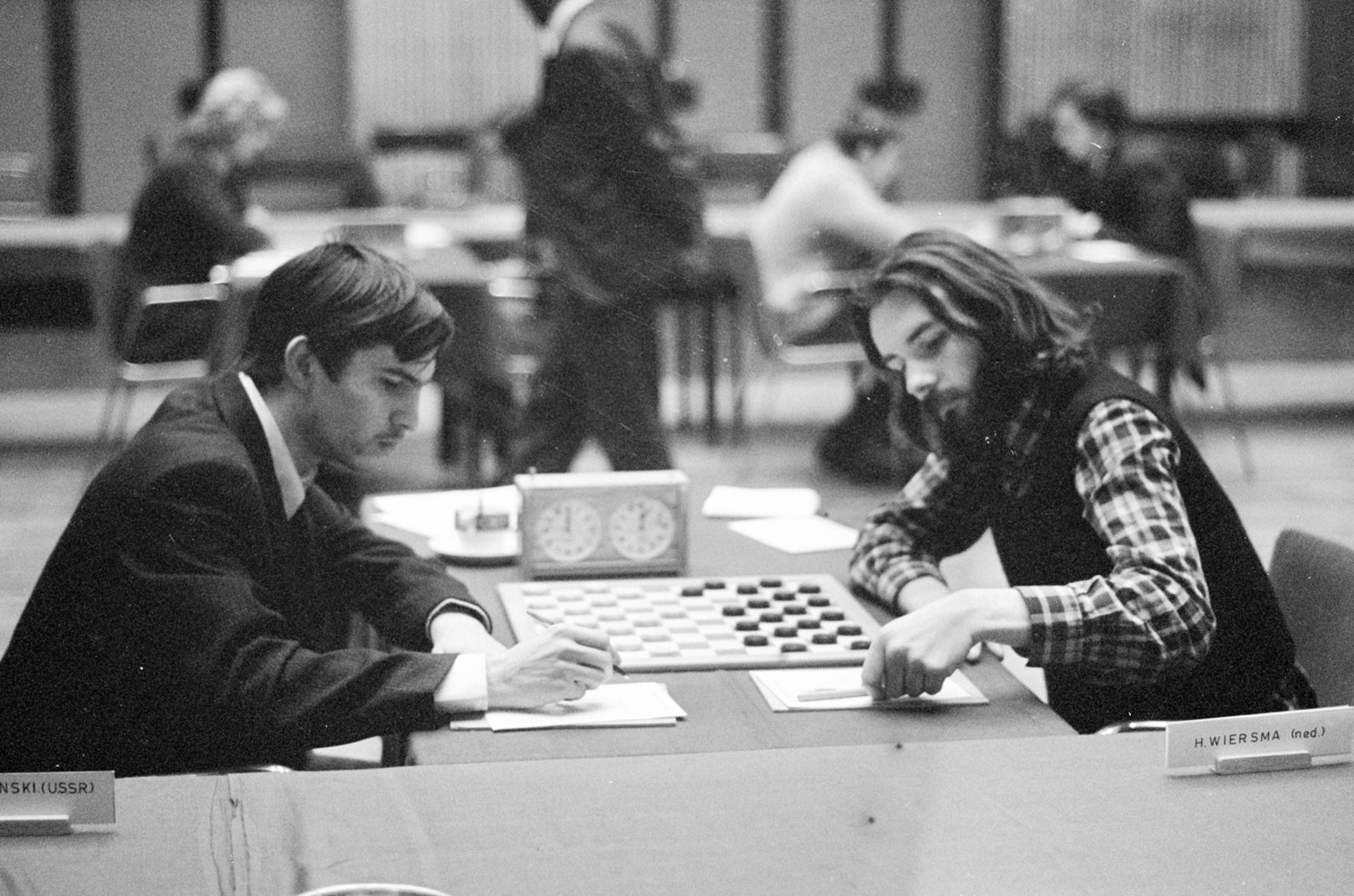

I mention this match because both of the main players in the game we're highlighting here were present at that event — namely, Nicolai Mistchanski and Alexander Mogilyansky.

At the time, it was quite special to see these players in real life. Back then, all I had were plain tournament booklets with game notations — no photos or images of the players.

The final of the USSR Championship, in which the featured game was played, consisted of 18 participants playing a round-robin tournament. The last USSR Championship was held in 1991, and it was won by none other than Alexander Shvartsman!

Not long ago, I began reconsidering my opening repertoire, wanting to introduce some fresh ideas here and there. As the years go by, certain habits can set in — and if you’re not careful, you eventually stop noticing them, earning yourself the label of a “routine player.” I try to stay alert to this, and in my draughts workshop there’s always some work in progress or preparation underway.

For Damkunst, I thought it would be interesting to take the reader along a bit on the theme that led me to the Mogilyansky–Mistchanski game.

When it comes to openings in draughts, especially now that many years have passed, I like to reach positions fairly quickly where the players must rely on their own understanding and where there’s always something interesting to be gained. The study I’ve put into this is mainly focused on avoiding such dullness that one could call it game spoiling. Of course, the outcome isn’t just a matter of technique but also of personal taste.

Anyway, I found myself stuck in the habit of responding to 1.34-29 with the sequence 19-23 2.40-34 14-19 3.45-40 and then 10-14. Often this was followed by 4.50-45 5-10 and 5.29-24, and so on. I no longer wanted to play that line of play, so I decided to explore the game that arises after Black’s sharp 3…20-25(!). Then came 4.32-28 23x32 4.37x28 10-14, and from there I began my research.

Usually, White players move to square 24 and continue with 5.29-24 and so on. When I wondered what would happen if White decided to forgo square 24 and instead remained in the center for the time being, I came across the following game — one that could just as well have been played in a contemporary top-level tournament: